Abbiamo 259 visitatori e nessun utente online

The supremacy of finance

from “ La crisi del capitalismo – Il crollo di Wall Street” Ed. Ist. Onorato Damen – Jun 2009.[IT]

From 1980 to 1982, while the gross growth of fixed capital in the OECD countries was on average of the 2.3%, the financial capital one was of the 6%. Simultaneously, the financial transactions have by this time reached such a big dimension that only the 2% of capital movements corresponds to service and goods exchanges.

In the great majority, the bourgeois economists and the financial operators, in the face of this widespread phenomenon, even when it heralds deep crises such as the one that recently has beaten down on the Asiatic financial markets, exalt it, since they imagine it at the same time as an out-and-out Eldorado, a new inexhaustible source of enrichment and development and a natural phenomenon as well as rain and drought, which however finds in the market forces capable to hold back it and restore the balance every time there are excesses in one sense or another. Not many people, instead, perceive its implicit risks and request remedial actions before it explodes. For some time now, among these ones, it’s worth signalling the presence of the famous American financial expert and plunger Soros.

He has recently warned on the American press that if we don’t reconsider our conception, our way of viewing the market, we’ll risk a collapse because we are creating global financial markets without understanding their nature. It’s a common idea, based on a wrong theory, that the markets, abandoned to their own mechanisms, tend to be balanced. And he urges, in order to give stability to the markets, their “international regulation”. However, if it’s true that the idea that the markets tend to be balanced by their own virtue is wrong, it’s the same for that one which considers that their regulation in a stabilizing perspective is possible and sufficient to bring back the financial sphere and the speculation connected to it in more limited ranges such that it doesn’t expose the whole system to the risk of a sharp fall. Indeed, both the abstract from the fact that the boosts to growth and globalization of the financial spheres come from the contradictions of the capitalistic accumulation process which caused, at the end of the 1960s, a fall in the average profit rate such that it led increasing capitals to look for their remuneration in speculation.

The parasitical surplus appropriation, marginal until capitals found adequate remuneration as industrial capital, has little by little grown, going beyond the limits expressly set in the first half of the 1930s and in the aftermath of Second World War, producing so deep changes in the monetary systems and in the interconnections between these ones and the world financial markets that they design the phenomenon of the financial sphere prevalence and of its globalization not simply as an occasional one, an anomaly (and so circumscribable through the introduction of rightly administrative corrections), but the landing place reached by the process of surplus appropriation in this phase of Capitalism.

From the coin money to the credit money

Money is not something falling from the sky (like the “Manna from Heaven”, as Milton Friedman, the famous conservative economist, would like to let us believe), but, on the contrary, it is a very complex social institution subject to historical changes.

And it has – we add – to obey to the requests of the system conservation, flexibly adapting itself to the needs of capital valorisation as they determine in relation to the development level of the productive forces and, in this context, to the trend of the capital accumulation cycle. After all, the same system of administered finance had replaced, under the boost of the 1929 great crisis, the system based on the convertible currency anchored to gold which, even though it assured for a long time a remarkable stability, at a certain point, was not able anymore to satisfy the new needs of the capitalistic accumulation process just like they were coming up by means of the development of the large-size industry and the industrial production on a large scale. For this reason, in 1931, through the Roosevelt New Deal in the USA, and then little by little in all the other countries a more flexible monetary system was created, based on the credit or bank money in place of the goods money, as it could be definitely be considered that one on which the previous system pivoted, so moving on from an endogenous regulation system of the monetary mass to a regulation system administered directly by the State through its central bank.

The central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the USA, could straight intervene on the money offer, changing its circulating amount, or indirectly, regulating the creation of money by the commercial banks (issue of bank cheques guaranteed by loans granted with parts of the amounts deposited in them, advances on credit bonds, etc.). But just when the new monetary system gave a central role to the bank money, it counterbalanced the fundamentally changeable nature of money creation justified by the profits of commercial banks with a set of rules separating these ones from the other financial intermediaries and which, unlike the other industrialized countries (Germany, France and Japan), limited greatly their access to the national bond markets. The instruments of monetary policy, such as the open market operations (placement of government bonds) or the regulation of the deposit remuneration and the loan interests, with pre-fixed top rates, have allowed the Fed to maintain low its interest rates, guaranteeing at the same time to the banks a differential of valuable return between the deposit remuneration and the loan rates.

The creation of money under the control of the central bank, proved functional to the expansion needs of the - to use a current expression – Fordist accumulation rising regime since it allowed to direct great amounts of financial capital towards the development of the productive basis, both through the financing in deficit of the public expenditure and the easy credit terms granting and by increasing the consumers’ spending power through the low interest rate loan granting. Besides, with Bretton Woods Agreement, signed in 1943, also the international payment system was someway based on the credit money administered by the State as the dollar, even though declared convertible into gold in a ratio of 35$ per ounce, was actually convertible and could be exchanged with the other currencies in a prefixed exchange rate, according to the rules established by the agreement. In the western industrialized countries, the 1950s and 1960s mighty development would have hardly occurred if economy hadn’t availed itself of the ductility of the new monetary mass regulation system and of the international financial stability warranted by the fixed exchange regime.

The crisis of the administered finance and the overcoming of Bretton Woods

When at the end of the 1960s, in the USA and then in the rest of the industrialized world, the decrease of the average rate of profit got a statistical relevance in absolute terms, too, this system, that was unanimously considered the cure-all by which Capitalism had been able to defeat its own contradictions, showed the first fissures. In the general opinion that the decrease of profits and wages was a present-day fact reabsorbable in a short time, the FED, in order to support the aggregate demand in procyclical function, marked down the interest rates facilitating the public and private indebtness. The banks, in turn, aiming at containing the profit decrease, bypassed the limits imposed by the FED in loan granting, creating new short-term monetary instruments (sale and repurchase agreement, negotiable certificates of deposit, etc.). The indebtness incurred by the American banks in these new forms passed from the 2% of the entire loss in 1965 to the 21% in 1978, giving life to an out-and-out process of credit money creation out of government control [6]. Moreover, the widespread presence in the several productive sectors of monopolistic and oligopolistic positions made possible for many firms the safeguard of their own profit margins through the finished product price rise. Monetary mass stagnation and expansion, incentivized by the indebtness growth, caused the simultaneous inflation growth and the productive capacity underestimation. This phenomenon, never observed before, so that it was indicated by having recourse to the neologism ‘stagflation’, allowed a soft management of the crisis avoiding sudden fall-downs, but it also provoked devastating dynamics which in a short time would have made emerge other and no less painful contradictions. In the stagflation origin and management an important part has been played by the State, which in its twofold role of debtor and, as credit money producer, creditor in the end – as the above mentioned Guttmann underlines: has allowed the socialization of the private losses and risks by dividing them among all those who used the national currency. Such a monetary stopgap has furthermore made softer the brutal adjustment connected to the indebtness deflation, avoiding the massive destruction of capital that had been a characteristic of the previous economic depressions [7].

The steady growth of the monetary mass without a corresponding both economic and of the golden reserves growth, as planned by Bretton Woods Agreement, caused an overestimation of the dollar so that the whole fixed exchange system could be impaired. Even from the end of the 1960s, with the first decline signals of the average profit rate, first of all the big American multinational firms and, in a smaller degree the British ones, encountering growing difficulties in giving a return to the capital invested in the productive field, started to hold back a growing amount of the profits gained abroad at the banks in London in the so-called off-shore sector, giving rise to the euro-dollar market, a real financial market parallel to the official one, characterized by a strong propensity to speculation.

The overestimated dollar was a too favourable occasion to miss it, all the more so that powers like Japan and Germany pressed to obtain the rebalancing of the parity among the dollar and the other industrialized countries’ currencies, because they were forced, in order to pay their importations first of all of oil, to buy dollars at a higher price than their real value, taking up a great share of the American inflation. So, more and more massive speculative waves started to beat down on the already weak payment system based on the fixed exchange regime.

In the attempt to contain speculative waves trying to low the dollar’s value, the president Nixon, at the beginning, in August 1971, declared, in an official way, too, the inconvertibility of the American currency, and then, in March 1973, repudiated the Bretton Woods Agreement, getting rid of the fixed exchange system. The resulting dollar’s devaluation gave a certain breath to the American industrial system, but it quickened the inflationist process which reached double figures rates. And inflation if on the one hand allowed to control somehow the industrial profit decrease through the price rise and the automatic wage devaluation, on the other hand put into action a kind of “nominal accumulation process ” [8], as confirmed by the table 1 showing the progressive percentage gap between the GNP growth rate and the general price level one in the main industrialized countries.

|

Table 1 — Economic growth and inflation in the main industrialized countries (United States, Japan, France, Italy, Great Britain and Canada — Source OECD) |

|||

|

- |

1970-79 |

1980-89 |

1990-95 |

|

GNP growth % |

3.6 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

|

Price rise % |

10.7 |

5.1 |

3.3 |

At a certain point the financial capital, too, caught in the grips of the monetary devaluation and of the low real interest rate (see table 2), had compromised any chance of self-valorization so it boosted the FED to change radically its monetary policy. And a change of course became necessary to better face the crux represented by the double deficit of the commercial balance and the public one which hoarded in geometrical progression. In October 1979, the complaint was heeded by the then-President of the American central bank Volker who put an end to the long season of low interest rates, starting a savage control on the monetary mass and abolishing all the aids to easy credit. Six months later, in consequence of the abolition of the liens on deposits and bank loans, the controlled credit system was definitely abolished, too.

|

Table 2 — Evolution of the long term interest real rates (Annual average rates as percentages) |

||||||||

|

- |

1960-69 |

1970-79 |

1980-89 |

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

|

France |

1.5 |

-0.5 |

6.8 |

8.2 |

7.1 |

7.6 |

5.2 |

5.7 |

|

USA |

1.1 |

-0.3 |

6.5 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

|

Germany |

2.5 |

3.2 |

4.9 |

3.3 |

4.6 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

|

Italy |

0.4 |

-6.1 |

5.3 |

9.1 |

8.8 |

10.6 |

8.4 |

7.2 |

|

Great Britain |

1.7 |

-3.0 |

5.8 |

7.5 |

6.7 |

6.9 |

5.1 |

5.6 |

|

Japan |

1.2 |

-0.1 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

4.7 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

|

Average G7 |

0.8 |

-0.5 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

The monetarist turning point

The abandon of the fixed exchange and central controlled cut rate system gave birth to, first in Great Britain and then in the USA, a series of reforms whose aim was dismantling the demand support policy by means of the financing in deficit of the public expenditure; such policies were held responsible for the crisis and were inspired by the Keynesian economic theory.

In its place and against it – as the economist M. Albert writes – some new trends come to light: the supply side economics theorists and the monetarists, which, following the leading figure of the “high priest” Milton Friedman, propose an opposite policy [9].

Monetarists, confusing or pretending to confuse the capacity of money to turn into wealth with wealth itself, consider the financial sphere able, just like the productive one, to generate surplus and since, like for the Pre-Ricardian economists, for the monetarists, too, surplus is produced in the goods circulation phase, the free money circulation on a larger and larger scale would have offered a new model for a new development phase. First Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain and then Ronald Reagan in the United States acted as champions of the new economic thought, by removing any obstacle to the free economic and financial activity. In the USA with Reagan’s election many spectacular reforms were undertaken. The climax of this policy is the ERA (Economic Recovery Act) – as A. Michel also writes. It involves three essential elements: the deregulation in oil, broadcasting, air transport, bank and competition sectors; a large reform of the tax system, reducing the fiscal pressure particularly on the highest incomes; the struggle against inflation carried on through the drastic control of the monetary mass. The immediate consequence is that the price of money rises and the party is over. The interest rates, indeed, will reach incredible levels, even surpassing the 20% in 1980-1981. So the dollar rises and rises, until it exceeds the threshold of 2000 Liras in 1985 [10]. As we can see in the table 3, in these years the interest rates become positive again. At this time, the turning point is completed: there is a change from the economy based on the support to the aggregate demand through the system of controlled credit ( low interest rates) to an economy based on the direct support to financial capital, through the control of the monetary aggregates and the interest rate and exchange regulation assigned to the market.

|

Table 3 — The American real interest rates rise after the liberalization — Source: Council of Economic advisors. The Economic Report of President, U.S. Government — NB. The Treasury returns are reduced by the GNP deflector, the returns of the bonds issued by private companies are reduced by the production price index, the returns of the private mortgage loans are reduced by the consumer price index. |

||||||||

|

- |

1960-69 |

1970-79 |

1980-89 |

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

|

France |

1.5 |

-0.5 |

6.8 |

8.2 |

7.1 |

7.6 |

5.2 |

5.7 |

|

USA |

1.1 |

-0.3 |

6.5 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

|

Germany |

2.5 |

3.2 |

4.9 |

3.3 |

4.6 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

|

Italy |

0.4 |

-6.1 |

5.3 |

9.1 |

8.8 |

10.6 |

8.4 |

7.2 |

|

Great Britain |

1.7 |

-3.0 |

5.8 |

7.5 |

6.7 |

6.9 |

5.1 |

5.6 |

|

Japan |

1.2 |

-0.1 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

4.7 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

|

Average G7 |

0.8 |

-0.5 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

This strategic change in the American economic policy has obeyed, in relation with the needs of a decreasing accumulation process, to the same logics through which the USA in 1945 had imposed on the allies and the losers the Bretton Woods Agreement: at that time, in order to exploit to the full the advantage of being the world greatest industrial power, thanks to its 40% of the entire world industrial production, now in order to impose its financial excessive power, based on what M. Albert calls the monetary privilege.

Since from 1945 (Bretton Woods Agreement) the dollar has served as reference currency in the international transactions. It has also represented the main currency of the central bank monetary reserves. What an extraordinary imperial privilege is that of paying, borrowing, financing its expenditures with its own currency! A privilege that in truth is by far greater than we usually think. The American economist John Nueller explains it without beating around the bush: just imagine for a moment that all the people you meet, accept in payment the cheques you print. Add to this, that the recipients of your cheques all around the world don’t cash them in and use them as money to pay their expenses. This would have two important consequences for your finances. The former would be that, if the whole world accepted your cheques, you wouldn’t need any more to use money, your cheque book would be sufficient. The latter consequence would be that, viewing your statement of account, you would have the surprise to find a balance greater than the amount you didn’t spend. Why? Because of the reason we said before, the cheques printed by you would circulate (from one hand to another), without being never cashed in. Starting from this reasoning, Nueller states that: the USA have had the use of five hundred billions of dollars more than those collected through the levies paid by the American taxpayers and the bonds subscribed by the American or foreign savers. So America rules on money, its own and the other’s one. The dollar is at the same time the sign and the instrument of this power [11].

The USA have completed a way which has led them to move the cornerstone of their hegemony from the power of their industrial system to that of their financial power by exporting their own inflation and then by the policy of high interest rates and of the support to the offer rather than to the aggregate demand. The risk of a colossal financial crack was prevented thanks to the high interest rates. The public debt financing could be guaranteed by means of the surplus inflow of the capitals accumulated in particular by Japanese and Germans since their trade balances were positive and a great mass of Euros and petrodollars were in circulation. Every other state adopting such a policy would have been choked by so high rates , but the USA, being able to face them through the simple issue of cheques printed by themselves, took enormous advantages of this situation. The countries of the so-called Third World, which until that moment had been flooded by inflated dollars, were suddenly forced to face a dizzying revaluation of their foreign debt and of the interests bearing upon it. The increase was so great that they turned from importers into net exporters of capitals and many times the debt service cost became by itself equal to their entire GNP [12]. The financing of the military system restructuration, depending on their anti-soviet policy, that used up over 500 billions of dollars, couldn’t have been even imagined if they didn’t have thought up a way to make the world community pay the costs. The banks took huge advantages, too. Many of them, at this point on the edge of failure because of their great debt exposure accumulated in the previous years towards the peripheral countries, were finally able to fill out their profits and the commercial banks, thanks to the abolition of the restrictions provided for by the previous bank law, could put more effort into the simple financial investment.

The table 4 shows the change of their income sources in the period 1974-1994. The advantages for the large size industry, that of the great multinationals above all, weren’t smaller. Owing to the fact that the dollar was overrated, the mass of dollars accumulated through that kind of nominal accumulation process based on inflation resulted overrated, too, and so they were able to finance the offshoring process of the productions with a high content of variable capital in the areas where labour costs were cheaper and at the same time to increase the investments in the new high-tech sectors such as information technology and telecommunications. These investments were stimulated by the military system restructuration project due to the application in the war sector of micro-electronics and all the technologies connected to it. An emblematic example was that of the space shield which by itself took more than 250 billions of dollars “the 10% of them only for the research” [13]. We omit here the exam of the consequences that the monetarist turning point has had in the development of the industrial globalization process and the resulting new international work division and the work market liberalization which Prometeo has already dealt with [14].

|

Table 4 — The transformation of the commercial bank income sources — Source Kaufman and Mate (1994) — From: La mondialisation financière |

||

|

- |

1974 |

1994 |

|

Financing of loans to non-financial operators |

35.7% |

22.6% |

|

% of common funds managed from banks |

7.0 % (1983) |

- |

|

Incomes without interests in % on the total of the banks incomes |

21% |

34.3% |

Here we are interested in highlighting the consequences that this turning point has caused in the relations between the financial field and the industrial one. During the Keynesian phase the creation of money and its derivatives had been thought, organized and subordinated to the productive basis development assuring good profitability to the capitals invested in it. The monopoly exerted from the state on the creation of money was therefore functional to the necessity to keep the interest rates (the money price) low and constant in the course of the time, relating to the needs of the industrial investments multi-year needs. The determination of their level, consequently, couldn’t be committed to the market but it had necessarily to be controlled in order to give assurance to the programmed cost prevision and the same for the exchange rates. The exchange rate, in fact, is none other than the currency price on the international market and it is strictly connected to its domestic price (interest rates); the interest rate control would have been useless without a fixed exchange system allowing the currency fluctuation control within very strict limits. On the contrary, when the industrial profit average rate decreased and it was necessary to complete it with extra-profit growing quotas, the currency was thought and organized as value producer. But since, in contrast with what monetarists affirm, it can, through its fluctuations, just transfer the value among different places and people but not create it, it was needed facilitating its movements by removing all the obstacles so that the value migrations from and to every place were made possible. The exchange market liberalization at first and then the interest rates one obeyed to stringent support needs of the capitalistic accumulation process through the surplus parasitic appropriation.

The growth of the financial sphere

If on the one hand liberalization and the consequent financial globalisation resolved many of the USA and Great Britain’s problems (we shouldn’t forget that, after the dollar, the pound was the most used currency in the international payment and that London is even now one of the world most important financial marketplaces), on the other hand they gave the ‘incipit’ to an expansion process of the financial sphere without precedent in Capitalism history. At the beginning the main contribute to the growth of the financial sphere and of the speculative activities to it connected came exactly from the governments that in order to facilitate the financing of their balance deficit through the Treasury bill issue, gave rise to the bond market not subject to any restriction and open to the foreign capital. In those years, the public indebtness underwent an out-and-out explosion. For instance, the total one of the European countries, including also the local and social administrations one, moved from an average of 32% of the GNP in the years 1961-1973 to the 58.8% in the years 1987-1994 and it reached, in 1995, the 70.6% [15].

The growth of the American one was even spectacular, since it moved from 1000 billions of dollars in 1980 to 4000 in 1992, quadrupling in just 12 years the debt accumulated in the two previous centuries. The USA, in particular, with a public debt, according the IMF, equal to the 39% and, according a McKinsey research, to the 50% of the debt of all the OECD countries put together, have been the driving force of the birth of what F. Chesnais calls ‘the regime of creditor dictatorship’, by issuing lots of high profit Treasury bills.

The public bond markets – he writes – have become the support of the international bond markets, the place where the 30% of the world financial assets guaranteed by constant and liquid returns (liquidity is assured by the secondary markets where bonds are permanently negotiable) [16].

Once started, this imposing financial market has acted as a real magnet for all those institutions which, living on the collection and the management of the financial capital, are always looking for investments with a high degree of liquidity. In particular, the individual retirement accounts and the funds which just in those years knew an extraordinary development that the commercial banks were forced, with their competition, to a deep diversification of their saving collection instruments and of their income sources, giving, as we can also see in the table 4, a strong boost to their fund activity. The individual retirement accounts have to be discussed apart. They originated in the Anglo-Saxon world as private institutions, with the function to collect funds, made up by the worker and firm compulsory dues, aiming at assuring the workers themselves a constant and guaranteed retirement fund. Thanks to this compulsory accumulating mechanism, until the jobs increased and the number of the incoming workers exceeded that of the outgoing ones (retirees), the collected funds were always higher than the disbursements and consequently the profits on accumulated principals and interests, even though the rates were not very high, were more than enough to guarantee good returns to the management and stability and assurance to the retirement funds. Things changed when the occupation trend reversed and the inflation burst.

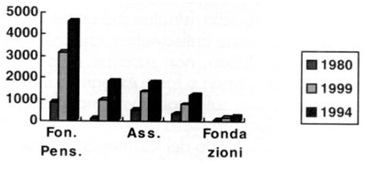

On the one hand, the inflation facilitated them, devaluating the pension value in relation with the contributions previously paid and increasing their liquidity; on the other hand, the job reduction, causing also a fund collection reduction, boosted them more and more towards the short term and high liquidity investment. Facilitated by the interest rate increase and by the dollar revaluation in short time they have become the fulcrum of finance and international speculation ( see graph 1).

|

Graph 1 — Financial assets evolution in relation with investor types from 1980 to 1994 |

|

|

The American retirement fund assets, for instance, jumped from 667.7 billions of dollars in 1980 to 3571.4 in 1992 and, according to the IMF data, as the ones just above mentioned, in the main OECD countries, the total assets of the financial institutions (retirement funds, life insurance companies, insurance companies and common investment funds), moved from 1,606.9 billions of dollars in 1980, equal to the 59.3 % of the USA GNP, to 8,008.4 billions of dollars in 1992, equal to the 125.6% of the USA GNP and to the 165.3% of the Great Britain one [17].

Derivatives

The enormous growth of the financial capital mass looking for strongly profitable and high liquidity investments has had as immediate result the market transformation into an essentially financial market and the birth of a new series of financial products. A new line of high risk and profit products has added to the old terminable contracts making the world economy a huge casino. Some of them, the swaps and the currency options, were born to limit the risks connected to the interest and exchange rate fluctuations. Other, such as the junk bonds, to facilitate the most reckless speculations on the stock market. But we will examine in depth above all the stock options and the currencies because of the effects they have had on the world macro-economic flows.

As concerns the junk bonds, it is enough to say the they are bonds issued by private companies and guaranteed only by a high profit promise. That is, face to their emission there are neither the assets of an industrial firm or an estate company, nor any kind of patrimonial goods, but just a promise based on the presumed issuer’s ability to succeed in exploiting in its own favour and in the junk bond underwriters’ favour, who will be remunerated with very high rates, the stock quotation variations caused by the investment of the collected capitals.

Now let’s get to the options. According to what the philosophy historians hand down, the options inventor would have been Thales. As Aristotle tells, in order to deny the accusations of poor practicality to him addressed because of his perennial distraction, having foreseen for that year, according to his astronomical calculations, a rich olive crop, he paid, a long time before the harvest, the right to rent the local oil mills at a pre-established price. At the moment of the harvest, since the prevision came true, the olive mill high demand raised the price so he, subletting them, could make money out of the difference between the paid rent and the cashed in one. If his prevision would have resulted wrong, he, instead, could have renounced to rent out the oil mills, just losing the sum paid to obtain the right to do it.

From Thales to the stock and currency options, the step has been long, but technically short. In the 1970s the Chicago stockbrokers, in order to reduce the risks connected to the stocks trading activity, created the “stock rights option”, also known as stock underwriting right. In the previous terminable contracts, both the buyer and the seller engaged themselves to buy or to sell a certain amount of bonds at a fixed price. The buyer ran the risk that if, at the contract expiry, the bond quotations would be lower, the bought shares would have lost their value and he would have paid more for something that cost less on the market. The seller, on the contrary, ran the risk, in case of rise, to have to sell his bonds at a price lower than the market one. Besides, if he had sold uncovered bonds, that is without owning them, he would have had to buy them at the market price and to sell them again at the lower one agreed at the contract stipulation. It was as if Thales rather than buying the right to let the oil mills at an established rent and presumably, given the prevision of a rich crop, lower than the market one, had stipulated an oil mill rent contract. In case of a poor crop, he would have had to pay the total rent anyway with an enormous loss, both since the rent would have been lower than the one paid by him and because many oil mills would have remained unlet. The new options, instead, offered a way to move around. The buyer of a society bond purchase option (DONT premium contract) paid the righty to buy the shares at a certain price, called strike price. If the bond quotation had increased above the strike price, the DONT premium contract buyer would have been able to require its delivery and to buy it, earning a profit from it. The same happened for the sell options, the PUT options (premium sells). If the price had decreased, the option holder could have bought the shares at the market price and exercise the sell option at the more profitable strike price [18].

Both of them, in case of a wrong prevision, a very probable fact in high inflation periods, could have renounced to buy or sell the bonds, taking only the loss of what they paid for the option purchase. In this way, the risk connected to the normal fluctuation of share quotations could be reduced, too.

The holder of a share block could buy some PUT options in order to guarantee himself from a quotation fall. If the share price had decreased, these option value would have increased and the losses on the investor’s shares would have been balanced on the options [19].

But very soon, options became something more than an insurance policy. Since they didn’t envisage, as the old terminable contracts, the real bonds handover, the options could have been issued in an unlimited number and so the big financial management centres found themselves in possession of a strong control instrument for the share market and an excellent income source. The options, in effect, even if they were something different from the reference bond, could influence the market trends, in one sense or another. So, while in the past the bond quotations, in relation with the company economic trend, produced earning and losses, now the roles reversed. The one who had big amounts to invest in options could influence the quotation fluctuation to his liking and realize, at the right moment, enormous earnings. Such an innovation had immediate repercussions on the market: from a place essentially dedicated to the saving collection in order to finance the productive investments, it changed into a place where the financial capital, exploiting its command power on the economy, realizes basically speculative profits. So the birth of options, junk bonds and the OPA liberalization (tender offers), boosted to a kind of capital accumulation, realized fundamentally through the firm annexations, releases and mergers.

The mergers and the takeovers – the economist Edward J. Epstein observes – of course aren’t something new: from at least thirty years the American companies resorted to them in the aim of increasing their market quotation, diversifying the risks, improving their balances, but while the mergers and the conventional takeovers, above all when a group began an operation, aimed at the growth of the group itself and they worried only in a second moment about possible temporary reductions of the share value, the recent OPA aimed instead at the rise of them [20].

And – we add – at strengthening the monopolistic power of the by now big transnational firms ruling the world [21].

But this insane mechanism, this kind of financial delirium – as M. Albert calls it – by which someone thinks it is possible to replace the real production of richness with that of the paper money, extended in short time from the stock market to the currency ones. Until 1971 the only way to buy or sell foreign currency consisted of addressing to a bank, which at its turn had to let know all the currency operations to a specific governmental office and it authorized them only if there was an effective correspondence of a real goods movement. The exchange fluctuations were in this way very small and easily governable by the IMF and the World Bank that were designated to this role.

However in 1971 – under the pressure of the bank lobbies connected to the newborn euro-dollar market (editor’s note) – the Monetary International Market was founded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and it began to negotiate the currency futures. The futures were similar to the terminable contracts, but they didn’t need the involvement of banks. But, like the terminable contracts, the future contracts were binding commitments: neither of the two parts could have changes of mind [22].

Anyhow, they assured more freedom of action to the speculation. This was true until the first 1980s, when the instability of the currency market became so strong that it caused serious problems to the big multinational firms, above all the American ones.

For instance – the financial expert Millman writes –in order to buy Caterpillar tractors, the Canadians had to get dollars, but the dollars were at this point so expensive that a Caterpillar tractor cost one and half times more than a Komatsu one. The consequence was that although Caterpillar didn’t change its price in dollars, it was as it had done it considerably in the foreign markets where other currencies were used. And there wasn’t only Caterpillar. The German and Japanese cars became a familiar presence on the American streets. The business planners found themselves in the impossibility to draw up reliable budgets, because they didn’t know in what measure the courses of the currency exchanges would have weighed on the prices and on the competition [23].

There was only a way to limit the risks: to extend the options to the currency market, as it punctually happened. And Millman is right when he says that:

‘We need to go back to the paper money invention to find such an important innovation in the financial history. The central banks compare it to the discovery of nuclear power.’

According to him, committed monetarist:

The options (on currencies) are without any doubt the most powerful and versatile of the new financial instruments developed by the private markets in order to face to the economic chaos’ [24].

Well, this is a good example of the nonchalance through which the dominating single thought upsets reality. The following facts and the financial crises that had ensued in the last 15 years until the recent one, which has devastated the financial markets of the East-Asiatic countries, are the evidence of the exact contrary. The currency options, like the share ones or the swaps on the interest rates, as surrogates (derivatives) of bonds which issue is still subjected to controls, can indeed be created without limits and made for those who need to maintain positions of great liquidity and at the same time dispose of plentiful capitals to invest and all that is made in the interest of the big financial institutions. In this way, although they had been conceived to limit the currency fluctuations risks, they have become in short time one of the most powerful instrument at the financial speculation’s disposal. To such an extent that this activity, previously occasional, which usually developed at the moment of the inflation acceleration during the boom periods and susceptible of collapse when the cycle flexed, has become independent from the cyclical process and it represents an important source of income for the companies, the financial institutions and the individual savers [25]. And the currency options have facilitated this development more than any other innovation because, being a monetary derivative, they have those requirements of liquidity, mobility and universality alluring the speculation more than any other investment form.

The growth of the financial speculation – R. Guttman also writes – hasn’t been in any other place so emphasized as on the currency market. Nowadays currency operations represent in average 1,400 billions of dollars, of which only the 15% at most corresponds to commercial and long term capital fluxes. The rest is speculative capital, positioning itself so that it ensures in a short time the portfolio against the price risks and the profits on the exchange rate fluctuations [26].

This capital mass daily circulating on the world currency markets is so huge that at this point it eludes any control and so, whereas in the past the central banks oriented the financial capital movement, now the financial capital orients the central bank monetary policy and, consequently, the State economic one, too. For the smaller and weaker countries especially, this has meant the total loss of autonomy in the formulation of their own economic politics. The attack launched in 1987 by Andy Krieger, the Salomon Brothers expert in currency operations, on the whole monetary mass of New Zealand is by now a classic. It seems that Krieger with an investment of 100,000 dollars in currency options actually managed to control from 30 to 40 millions of dollars. Considering that he could move 50 millions of dollars, he was able to sell overdraft the entire monetary mass of New Zealand realizing profits that nobody ever succeeded in calculating exactly. Instead it is sure that New Zealand, in order to avoid being overwhelmed by the inflation, was forced to adopt a highly restraining monetary policy and to cut the social expenditure.

The supremacy of the fictitious capital

Already Marx, in the third volume of “Capital”, hints at a distinction between two kinds of financial capital: the one lent at medium and long term, producing profits, and the one called by him fictitious capital. The latter, unlike the former, is made up of credits exchangeable with bonds, such as the public debt bonds, whose value is not given by a direct return of productive capital, but by advance capitalisation of future incomes. Now, if we think out, the creation of credit money, whether monopolized and regulated by the State or set free, can take on both forms.

It is financial capital generating profits when it is lent against a productive investment, it is fictitious capital when it functions as departure base for the creation of further credit money. For instance, with bank deposits and their partial granting, banks create money by means of money itself. In a credit money regime, most of the monetary capital is therefore creation “ex nihilo”, starting from nothing, inside the bank system, as a future income prepayment and not as an expression of an already made income, resulting from the productive capital successful accumulation [27].

It is clear that the prevalence of the one or the other capital form depends on the monetary management: if it is regulated and aimed at the productive base development, the first form prevails; on the contrary, if it is released from any control and regulated and aimed at the money creation “ex nihilo”, the second one prevails, as it happens nowadays. The financial crises, periodically falling down on the world markets and then from these moving to the real economy, originate from the fact that, in order to finance their debt, the big financial groups, the banks, the States themselves are allowed to create credit money from money itself. Financial derivates in general and currency options in particular, that are exactly a value creation from nothing, are the picklock with which the fictitious capital can open any safe. Being able to concentrate an enormous capital amount thanks to the option multiplying effects, especially those on currencies, financial institution managers can make soar the quotations of any stock exchange list and any currency. When the peak is reached, that is when the big bubble is created, they hook it. Options are sold off and converted in reserve currency which, because of the reasons discussed before, is almost always the dollar. But during the escape, their fictitious nature unveils and they lose value. The list at the same time falls down and so does its reference currency. Those who have done rightly their sums and previsions make earnings with nine zeroes as if moneys were peanuts, others on the contrary lose everything. But it does not end here. Since every stock market is by now a local division of the big globalized financial market, the crisis of one market becomes the crisis of the world market. The central banks, in order to avoid bankruptcies with a domino effect, keep up the liquidity and the system embarks inflation. The investors which have gone away in time, foreseeing that the inflation will cause a rate rise and in particular of those of the devaluated currencies, concentrate on these last their swaps investments operating on the interest rates as the options on the currencies.

The investment is sure, you just have to wait: rates will rise and incomes will multiply. Monetarists, who believe that money is the centre of creation, observing that devaluation affects the weakest currencies, draw the conclusion that it had been overvalued because too protected by the State; so the IMF, that is the alcove of Neoliberalism and the world mighty, imposes, in exchange of the loans necessary to face the crisis, its remedy based on an further market liberalization, on privatizations and, in order to avoid that rising rates strangle completely economy, on cuts. Cuts in social expenditure financing, salaries, wages, pensions and in whatever else is regarded to as unnecessary. And since cuts are decided by rich people and rich people don’t eat bread, bread is almost always unnecessary. From a theoretical point of view, in this infernal cycle based on the inflation, deflation and capital destruction turnover, the reserve currency should undergo fluctuations specular to the single currency movements; but, since it is a world reserve currency and the movements of every currency converge on it, the endogenous inflation and deflation processes may be guided and moved to weaker currencies. From this we may gather that the Neoliberal thought represents exactly the contrary of what it affirms it wants to represent, because the free market defended by it, is actually the most refined command instrument in the monopolistic Capitalism age.

No way back

According to the dominating economic thought, the fact that you can get rich through the creation of pieces of paper, such as the options, is the substantiating evidence that it is possible, together with the traditional one, a more modern accumulation form based on the money movements and independent from the real economy. We are in the presence of a fictitious accumulation form that, among other things, has got in return just the growth of that debt they say they want to fight. What else is a future income anticipation if not a debt? And in fact in 1997 the world debt (including the firms, States and families ones) exceeded 33,100 billions of dollars, equal to the 130% of the world GNP and it increases by 6-8 % per year, that is beyond the quadruple of the world GNP growth [28].

The Neo-Keynesians, such as M. Albert, notice on the contrary that this economy, since it is based on liquidity, is a short term economy which doesn’t allow an appropriate investment planning to the detriment of the industry and the development and they oppose to it an up-to-date version of the Keynesian model. As in the 1930s, the alternative would be Capitalism against Capitalism. The critical evaluation of the economic thought recalling and at the same time inspiring the Neo-Reformism is instead more articulated. Even though it makes correctly derive the impetuous modification of the financial sphere into the main world economy sector starting from the crisis of the accumulation cycle, it admits the changeableness of the phenomenon. Its supporters’ aim is to contest the theories of the dominating economic thought, regarding to it as any other natural phenomenon, but they don’t notice that they end by supporting the possibility to overcome a structural crisis such as the accumulation cycle one by means of some legislative interventions.

Declaring that the financial hypertrophy and its procession of evils would be irreversible – F. Chesnais writes – means falling in a very suspicious form of historical determinism.

It would be a matter of giving to some social processes, products of the human activity, a similar statute as the biological evolution one [29].

But the alternative, for which we even wish a social clash radicalization, is entirely enclosed in a new and different monetary policy.

Because of the dominating current “laissez-faire” ideology – R. Guttman ends his essay – it will not be easy to push those who make the political decisions towards a concrete action in the sense of a new monetary regime establishing a correct balance between the function of money as a public or private good [30].

Even if we keep from any other consideration about this last twofold aspect of money, the basic idea is that we can choose between two possible monetary systems, as if the monetary systems were not a specific historical product of any phase of Capitalism, but something coming down, not like manna from heaven, but from one of its periphery districts: the politicians’ will. And so the monetarism critique arrives at monetarism.

Actually there are not two Capitalisms, neither monetary systems that could be adopted to our liking. The growth of the financial sphere and of the fictitious capital production has surely made the monetary deregulation its springboard. But deregulation has been caused by the falling of the average profit rate risking to swamp the entire world capitalistic system. It has helped to reinforce the dollar role in the world economic framework so that it made possible those surplus transfers without which there would not have been the compensation of the profit decrease in the USA and in the most industrialized countries.

Therefore the economy financialization is the specific product of the decreasing phase in the capitalistic accumulation process in the monopolistic capital era. In fact the big transnational industrial groups take advantage of it, too. Since most of the world commercial and financial fluxes pass through their hands, transnational firms can accumulate reserves in currencies more and better than any other one and with these operate on the currency markets in order to integrate their industrial profits with financial income sums.

The pressure put by the big European industrial groups in favour of the single currency arise just from the awareness that this integration, because of the low profit rates, has become of vital importance. The Euro, which in the official propaganda will help the tourists all around Europe to save the losses resulting from the currency exchanges, has actually as its main aim the creation of an area with a fixed exchange system for a better interest rate control and for a currency strong enough in the international context, functioning as a reserve currency alternative to the dollar.

In the end the expansion of the surplus parasitical appropriation forms is the logical evolution of a decaying system. Since the beginning of the 20th century Lenin observed this trend onset:

‘In the advanced countries there has been an overcapitalization. As long as Capitalism keeps being itself, the overcapitalization is devoted not to raise the masses’ existence level in a certain country, since a reduction of rich people’s benefits would derive from it, but to increase these benefits thanks to the capital exploitation in the underdeveloped countries. But unlike nowadays the capital exportation exercised, in the countries where the capital was introduced, a great influence on the capitalistic development, that is so accelerated’ [31].

For the capital owners, exportation ended cashing in the bond coupons in which the capitals had been invested, but the exported capital cycle ended with their transformation into industrial capital. In this way, the capital exceeding in an area contributed to enlarge the economic bases of the accumulation process and the parasitical appropriation could be compensated by a surplus additional production. Since this appropriation by now takes place, for the reasons observed before, above all by means of the fictitious capital production, the process results essentially in a surplus transfer towards metropolitan centres and towards those who hold the control of this special capital form production without any particular impulse to the growth of the economic sphere.

The result is a permanent general trend to impoverishment and devaluation of the labour force value on world scale. We are not in presence of an occasional phenomenon, but of the monopolistic Capitalism arriving at the most refined and advanced forms of the parasitical appropriation as an issue of the capitalistic accumulation process contradictions. Then, new monetary policies presuppose the opening of a new accumulation cycle, possible only through the generalized destruction of the exceeding capitals. In the meantime the financial crises, which at last are a surrogate of it, will intensify their occurrence concentrating richness and spreading misery.

December 1997

Notes

[1] Data OECD source taken from « La mondialisation financière : genèse, coût et enjeux », aavv, p. 63, Syros, Paris, 1996.

[2] Global village, International Index, Feb. 96, Alain Touraine, «The ideology of globalization».

[3] New Statesman taken from “La Repubblica” of 04-11-1997.

[4] R. Guttman – op. cit. p. 63.

[5] Ibidem, pp. 63-64.

[6] Ibidem, p. 65.

[7] Ibidem, p. 65.

[8] Ibidem, p. 65.

[9] Michel Albert, “Capitalismo contro Capitalismo”, ed. Il Mulino, 1993, p. 37.

[10] M. Albert, op. cit., pp. 37-38.

[11] Ibidem, pp. 41-42.

[12] For all that concerns the consequences of the monetarist turning-point on the peripheral countries’ debt or- according to the current terminology – underdeveloped, see “Prometeo”, n. 9/95, “Capitali contro capitali”.

[13] M. Albert, op. cit., p. 34.

[14] See “Prometeo”, n. 9-10-11-12-13, 5th series.

[15] Source: “Economie européenne” from “La mondialisation financière”, p. 105.

[16] F. Chesnais, op. cit., p. 27.

[17] Op. cit., p. 192.

[18] Gregory J. Millman, “Finanza barbara” – ed. Garzanti, p. 30.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Taken from M. Albert, op. cit., p. 79.

[21] See: Frédéric F. Clermont, “Le duecento imprese che governano il mondo”, “Le Monde Diplomatique”, apr. 1997.

[22] Ib.

[23] Ib., p. 35.

[24] Ib., p. 26.

[25] R. Guttmann, op. cit., p. 82.

[26] Ib.

[27] Ib., p. 67.

[28] Frédéric F. Clermont, art. cit.

[29] F. Chesnais, op. cit., p. 30.

[30] R. Guttmann, op. cit., p. 96.

[31] Lenin, “L’imperialismo fase suprema del capitalismo”, Munziano Editore, p. 125.